Building a GPS-Disciplined NTP Server with a Raspberry Pi - Part 1

Table of Contents

There’s something deeply satisfying about knowing the exact time. Not “close enough” time from your phone syncing to some pool server three hops away, but real time — straight from satellites orbiting 20,000 kilometers overhead. That’s what led me down the rabbit hole of building a GPS-disciplined NTP server with a Raspberry Pi.

What started as a mix of curiosity and a desire for better time accuracy on my home network turned into one of the most rewarding — and occasionally frustrating — projects I’ve tackled.

Why Bother? #

The short answer: because I could. The longer answer: NTP pool servers are great, but they’re subject to network jitter, asymmetric routing, and the general chaos of the internet. A local GPS-disciplined clock gives you a stratum 1 time source sitting right on your LAN. For a home lab, that’s about as good as it gets.

I also just wanted to understand how precision timekeeping actually works under the hood. Turns out, it’s fascinating — and more involved than I expected.

The Hardware #

For this build I used:

- Raspberry Pi 4 — I had one lying around from my previous Raspberry Pi Kubernetes cluster. You could probably get away with a Pi 3

- Waveshare GPS HAT — sits right on the GPIO header and provides both NMEA serial data and a PPS (Pulse Per Second) signal. This particular Waveshare model has a uBlox NEO-M8T GPS Module specifically designed for timing applications. It comes with a ‘Puck’ style GPS antenna which can be used to get you started.

- Waveshare PoE Hat — I didn’t want a bunch of cables trailing off the Pi. A PoE hat takes the connectivity required down to a single cable.

The Waveshare HAT is a solid choice for this kind of project. It breaks out the PPS line to a GPIO pin, which is critical for getting sub-microsecond accuracy. Without PPS, you’re relying on parsed NMEA sentences over serial, which can jitter by tens of milliseconds.

The Build #

Step 1: Hardware Setup. #

Let’s get started, attach the PoE hat to the Raspberry Pi and secure it with the supplied stand-offs. Place the GPS module on top of the PoE hat, attach the IPX to SMA pigtail connector to the GPS module and then finally screw the puck antenna into the SMA connector. It should look something like this:

Next up, we need to get an OS installed on the Raspberry Pi and make sure its booting correctly. My preference for a low-footprint OS on Raspberry Pis and other SBCs is DietPi. Simply download the matching image for your Raspberry Pi and write it to your SD card, I did so using balenaEtcher.

Once the copy completes, pop the SD card into your Pi and make sure it boots. DietPi has an interactive installer/configurator that runs on your first logon.

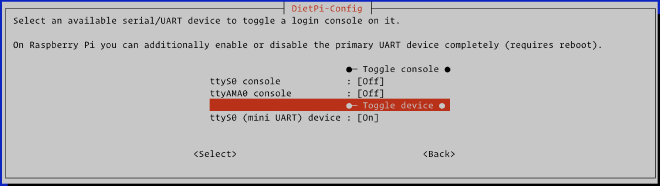

Once you are logged in, our first order of business is to disable the serial console that the OS enables by default. On DietPi we can achieve this by running sudo dietpi-config then navigating to Advanced -> Serial/UART then update the settings so they look the same as the image below.

Step 2: Firmware Configuration. #

Once that’s done, we need to make some config changes to /boot/firmware/config.txt, add the following lines to the end of the file with your text editor of choice (you will need to be root to modify the file.)

dtoverlay=disable-wifi

dtoverlay=disable-bt

dtoverlay=pps-gpio,gpiopin=18

enable_uart=1

init_uart_baud=9600

dtparam=eee=off

These settings accomplish the following:

dtoverlay=disable-bt— Disables the onboard Bluetooth hardware. On Pi 3/4/5, this also frees up the primary PL011 UART (which Bluetooth normally claims), making it available for other uses.dtoverlay=pps-gpio,gpiopin=18— Enables a PPS (Pulse Per Second) kernel driver on GPIO pin 18. This creates a /dev/pps0 device that receives the precise timing pulse from your GPS module, which chrony uses for nanosecond-level time discipline.enable_uart=1— Enables the serial UART interface (typically /dev/ttyAMA0 or /dev/serial0). This is how the Pi reads NMEA sentences from the GPS receiver for coarse time and position data.init_uart_baud=9600— Sets the initial UART baud rate to 9600, which is the default output rate for most GPS modules (including u-blox receivers) out of the box.dtparam=eee=off— Disables Energy Efficient Ethernet (IEEE 802.3az) on the onboard NIC. EEE introduces variable latency as the PHY transitions between low-power and active states, which is unacceptable for an NTP server where consistent, low-latency packet delivery matters.

Modify /boot/firmware/cmdline.txt and add nohz=off to the end of the existing line. It should look something like the following:

root=PARTUUID=45395152-02 rootfstype=ext4 rootwait fsck.repair=yes net.ifnames=0 logo.nologo console=tty1 nohz=off

nohz=off Disables the tickless (dynamic tick) kernel mode. Normally, the Linux kernel skips timer interrupts on idle CPUs to save power. With nohz=off, the kernel maintains a steady, fixed-rate timer tick (typically 250 Hz or 1000 Hz depending on kernel config).

This matters for a timeserver because the tickless mode introduces small, variable latencies in interrupt handling and timekeeping. A constant tick rate keeps the kernel’s internal clock stepping more uniformly, which improves the stability and accuracy of PPS timestamp processing and chrony’s time discipline loop.

Step 3: Software Installation & PPS Signal. #

Next up, we need to install some software that will interface with the GPS module to get the time information and serve it to clients on our network.

sudo apt update

sudo apt install pps-tools gpsd gpsd-clients python3-gps chrony

Once they are installed, go ahead and reboot the Pi. Once it comes back up run lsmod | grep pps. It should show you something like the following, this means the PPS module is correctly loaded.

aharrison-fuller@TimePi:~$ lsmod | grep pps

pps_gpio 12288 0

Assuming that worked, we can check the Kernel is receiving the PPS signals with the following command sudo ppstest /dev/pps0. You should see a new entry every second indicating the signal has been received.

aharrison-fuller@TimePi:~$ sudo ppstest /dev/pps0

trying PPS source "/dev/pps0"

found PPS source "/dev/pps0"

ok, found 1 source(s), now start fetching data...

source 0 - assert 1770372634.999966474, sequence: 1082 - clear 0.000000000, sequence: 0

source 0 - assert 1770372635.999966531, sequence: 1083 - clear 0.000000000, sequence: 0

source 0 - assert 1770372636.999967181, sequence: 1084 - clear 0.000000000, sequence: 0

source 0 - assert 1770372637.999966387, sequence: 1085 - clear 0.000000000, sequence: 0

source 0 - assert 1770372638.999966222, sequence: 1086 - clear 0.000000000, sequence: 0

Step 4: Configuring GPSD. #

GPSD is the software that interfaces with the GPS module over the UART bus to get the coarse time using NMEA sentences.

Edit /etc/default/gpsd as root and add the configuration below:

START_DAEMON="true"

DEVICES="/dev/ttyAMA0 /dev/pps0"

GPSD_OPTIONS="-n -G"

These options configure the following:

START_DAEMON="true"— Starts gpsd automatically at boot.DEVICES="/dev/ttyAMA0 /dev/pps0"— Tells gpsd to listen on two sources:/dev/ttyAMA0— the UART interface where NMEA sentences arrive from the GPS module (time, position, satellite info)/dev/pps0— the PPS kernel device on GPIO 18, providing the precise timing pulse- gpsd correlates both: NMEA gives it the “which second” and PPS gives it the exact edge of that second.

GPSD_OPTIONS="-n -G"-n— Start polling the GPS immediately without waiting for a client to connect. Without this, gpsd won’t read from the devices until something like cgps or chrony connects, which can delay getting a fix at boot.-G— Listen on all network interfaces (0.0.0.0) instead of just localhost. This allows remote clients to query gpsd over the network — useful if other machines need GPS data or you want to monitor it remotely.

After you have modified the file, reboot the Pi with sudo reboot

Step 5: Checking the GPS Fix. #

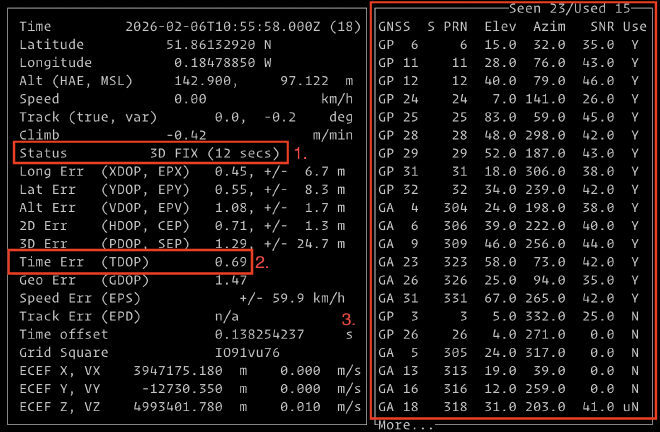

Once you are logged back in, run cgps. You should see an interface similar to the screenshot below:

I’ve highlighted the important sections of the interface

- A description of the current fix. You want to see “3D FIX” here.

- The Time DOP (Dilution of precision). Lower numbers are better, anything < 1.5 is pretty good.

- Satellite statistics, the most important number is the one at the top (Seen/Used). Typically, the more satellites used, the better the GPS/time fix.

Assuming you are seeing a 3D Fix and a low Time Error you are safe to proceed.

Step 6: Configuring Chrony. #

I chose chrony over ntpd for its faster convergence and better handling of intermittent sources. The configuration required setting up two reference clocks:

- The NMEA serial source (via a shared memory segment from gpsd) — this provides the coarse time, accurate to hundreds of milliseconds

- The PPS source — this provides the fine-grained correction, snapping the time to sub-microsecond accuracy

Getting these two sources to cooperate in chrony’s config took some iteration. The key insight was that the PPS signal tells you when a second boundary occurs, but not which second it is. You need the NMEA data for that. chrony needs to see both sources and understand their relationship.

Edit /etc/chrony/chrony.conf as root and add the following configuration:

# Welcome to the chrony configuration file. See chrony.conf(5) for more

# information about usable directives.

# Use Cloudflare and Apple NTP servers as network time sources.

# iburst sends a burst of requests on startup for a faster initial sync.

server time.cloudflare.com iburst

server time.apple.com iburst

# Use gpsd's shared memory (SHM 0) as an NMEA time reference.

# offset compensates for serial latency, precision reflects NMEA's ~1ms accuracy,

# poll 0 reads every 1s, filter 3 uses median of 3 samples.

refclock SHM 0 refid NMEA offset 0.080 precision 1e-3 poll 0 filter 3

# Use the PPS GPIO signal as a high-precision reference clock.

# lock NMEA pairs it with the NMEA source to determine the correct second,

# poll 2 reads every 4s, trust means this source is always considered reliable.

refclock PPS /dev/pps0 refid PPS lock NMEA poll 2 trust

# File to store the system clock's drift rate across reboots,

# allowing chrony to correct drift immediately on startup.

driftfile /var/lib/chrony/chrony.drift

# Uncomment the following line to turn logging on.

# log tracking measurements statistics

# Log files location.

logdir /var/log/chrony

# Stop bad estimates upsetting machine clock.

maxupdateskew 100.0

# This directive enables kernel synchronisation (every 11 minutes) of the

# real-time clock. Note that it can't be used along with the 'rtcfile' directive.

rtcsync

# Step the system clock instead of slewing it if the adjustment is larger than

# one second, but only in the first three clock updates.

makestep 0.1 3

# Get TAI-UTC offset and leap seconds from the system tz database.

# This directive must be commented out when using time sources serving

# leap-smeared time.

leapseclist /usr/share/zoneinfo/leap-seconds.list

# Include configuration files found in /etc/chrony/conf.d.

confdir /etc/chrony/conf.d

# Allow NTP client connections from any IP address,

# making this Pi serve time to the network.

allow 0.0.0.0/0

# Enable the chronyc settime command for manual time adjustments.

manual

# Advertise this server as a stratum 1 time source,

# indicating it is directly synchronized to a reference clock (PPS/GPS).

local stratum 1

Save the configuration and then restart chrony sudo systemctl restart chrony.service

run watch chronyc sources -v

➜ aharrison-fuller chronyc sources -v

.-- Source mode '^' = server, '=' = peer, '#' = local clock.

/ .- Source state '*' = current best, '+' = combined, '-' = not combined,

| / 'x' = may be in error, '~' = too variable, '?' = unusable.

|| .- xxxx [ yyyy ] +/- zzzz

|| Reachability register (octal) -. | xxxx = adjusted offset,

|| Log2(Polling interval) --. | | yyyy = measured offset,

|| \ | | zzzz = estimated error.

|| | | \

MS Name/IP address Stratum Poll Reach LastRx Last sample

===============================================================================

#x NMEA 0 0 377 0 +13ms[ +13ms] +/- 1000us

#* PPS 0 2 377 3 +333ns[ +409ns] +/- 160ns

^? time.cloudflare.com 3 9 377 137 -8014us[-8014us] +/- 18ms

^? frcch1-ntp-001.aaplimg.c> 1 9 377 653 -2959us[-2952us] +/- 12ms

^? leontp.adamhf.io 1 6 377 7 +1084ns[+1174ns] +/- 30us

Here’s how to read each column:

- Mode and State (MS, first two characters): The # indicates a local reference clock, while ^ is a remote NTP server. The second character shows how chrony is using that source — * means it’s the currently selected best source, + means it’s being combined with the best source, - means it’s a valid source but not currently being used, x means chrony thinks the source may be in error, and ? means the source is unusable or chrony doesn’t yet have enough data to assess it.

- Name/IP address: The identifier for the source — either the refid assigned in the config (like PPS and NMEA) or the server hostname. Long names are truncated with >.

- Stratum: How many hops away the source is from a reference clock. PPS and NMEA show as stratum 0 since they are the reference clock. Apple’s NTP server (frcch1-ntp-001.aaplimg.c>) and leontp.adamhf.io are stratum 1, meaning they’re also directly attached to a reference clock. Cloudflare shows stratum 3, meaning it’s two hops removed.

- Poll: The log₂ of the polling interval in seconds. A value of 0 means every second, 2 means every 4 seconds, and 9 means roughly every 8.5 minutes (512 seconds). Local reference clocks are polled frequently; remote servers less so.

- Reach: An octal representation of an 8-bit shift register tracking recent responses. 377 (octal) means all 8 of the last 8 polls were successful. If you see lower values, the source is intermittently unreachable.

- LastRx: Seconds since the last good sample was received.

- Last sample: The estimated difference between this source and your system clock. The xxxx value is the adjusted offset chrony is working with, and yyyy in brackets is the raw measured offset. The +/- zzzz is the estimated error bound. This is where the real story is told — PPS is showing an offset of just +333ns with an error bound of ±160ns, while the remote NTP servers show offsets and errors in the microsecond to millisecond range.

While chronyc sources shows you the time sources chrony is working with, chronyc tracking tells you how well your system clock is actually performing. Here’s the output from my timeserver:

Reference ID : 50505300 (PPS)

Stratum : 1

Ref time (UTC) : Fri Feb 06 11:34:58 2026

System time : 0.000000009 seconds fast of NTP time

Last offset : -0.000000003 seconds

RMS offset : 0.000000029 seconds

Frequency : 4.382 ppm fast

Residual freq : -0.000 ppm

Skew : 0.002 ppm

Root delay : 0.000000001 seconds

Root dispersion : 0.000000229 seconds

Update interval : 4.0 seconds

Leap status : Normal

Here’s what each field means:

- Reference ID: The source chrony is currently synchronised to. 50505300 is the hex encoding of “PPS” — confirming the GPS PPS signal is our primary reference.

- Stratum: This server’s stratum level as advertised to NTP clients. Stratum 1 means we’re directly synchronised to a reference clock, which is as good as it gets without being the reference clock itself.

- Ref time (UTC): The timestamp of the last update received from the reference source.

- System time: The current offset between the system clock and NTP time. At 0.000000009 seconds — that’s 9 nanoseconds — the system clock is essentially perfectly aligned with the PPS reference. Chrony continuously slews the clock to keep this value as close to zero as possible.

- Last offset: The offset measured at the most recent clock update. -3 nanoseconds means the last correction was almost imperceptibly small.

- RMS offset: A long-term rolling average of the offset, giving a sense of overall stability. 29 nanoseconds tells us the clock is consistently staying within tens of nanoseconds of the reference.

- Frequency : The inherent drift rate of the system clock’s oscillator. 4.382 ppm (parts per million) fast means the system clock would gain about 4.4 microseconds every second if left uncorrected. This is normal — cheap crystal oscillators on SBCs drift, and chrony’s job is to continuously compensate for it.

- Residual freq: The remaining frequency error after chrony’s corrections. -0.000 ppm means chrony is fully compensating for the clock’s drift — there’s essentially no residual error.

- Skew: The estimated error bound on the frequency measurement. 0.002 ppm means chrony is very confident in its frequency estimate. A higher value would indicate the drift rate is unstable or hard to measure.

- Root delay: The total network round-trip delay to the reference clock. Since PPS is a local GPIO signal with no network involved, this is effectively zero — just 1 nanosecond.

- Root dispersion: The total estimated error accumulated from the reference clock through to our system. 229 nanoseconds is extremely low and reflects the precision of a directly-attached PPS source compared to a network NTP server, which would typically show values in the millisecond range.

- Update interval: How often chrony is receiving updates from the reference source. 4 seconds corresponds to the PPS poll interval of 2 (log₂(4) = 2) that we configured.

- Leap status: Whether a leap second insertion or deletion is pending. “Normal” means none is scheduled.

Step 7: Profit #

At this point, your chrony stats should show accuracy to 10’s of nanoseconds. It’s time to distribute the time across your network via NTP. The exact method will depend on the device in question. NTP servers can typically be set manually on devices such as PC hardware, your router/DHCP server might let you configure NTP servers to distribute to clients if they don’t allow you to manually specify them.

I use Chrony on all my Linux/Mac machines to synchronise the system clock.

What I Learned #

- Antenna placement matters more than hardware quality. A cheap GPS module with a well-placed antenna will outperform an expensive one sitting indoors.

- PPS is non-negotiable for real accuracy. Without it, you’re just running a slightly fancier NTP client.

- chrony is excellent. It converged faster than I expected and handles the dual GPS+PPS source setup elegantly.

- The Pi 4 works great for this. You could use a Pi 5, but it’s overkill.

- Horology goes much deeper than this. Precision timekeeping is its own discipline — atomic clocks, Allan deviation, holdover stability. This project just dipped a toe in.

Was It Worth It? #

Absolutely. My home network now has a stratum 1 time source that doesn’t depend on an internet connection. Is the practical difference between this and a public NTP pool noticeable day to day? Honestly, no. But that was never really the point.

The point was learning how GPS timing works, understanding the full NTP stack from satellite to client, and the quiet satisfaction of running chronyc tracking and seeing those nanosecond offsets. If you’re the kind of person who finds that appealing, I can’t recommend this project enough.

What’s Next? #

I plan on writing some additional blog posts detailing:

- Some additional tuning of the OS you can perform to further increase accuracy.

- Designing and 3D Printing a custom case for the Raspberry Pi.

- Monitoring performance/accuracy with Prometheus and Grafana.

References #

As always, this project stands on the shoulders of giants, I used many references to get to this point. There are a few that I would like to call out explicitly: